It’s not always easy to draw a line between research and evaluation. The difference between them is a long-running debate with few clear answers. Some say evaluation is a subset of research; some say vice versa. Others see them as entirely separate things, or are unaware of a difference:

Why does it matter? In our experience, it matters because it drives the questions you ask when you’re commissioning an evaluation, and the kinds of answers you provide when you’re doing an evaluation. In turn, that can affect how useful your evaluation is.

Here are our thoughts on the key differences between evaluation and research. Understanding these differences can help commissioners and practitioners avoid common pitfalls.

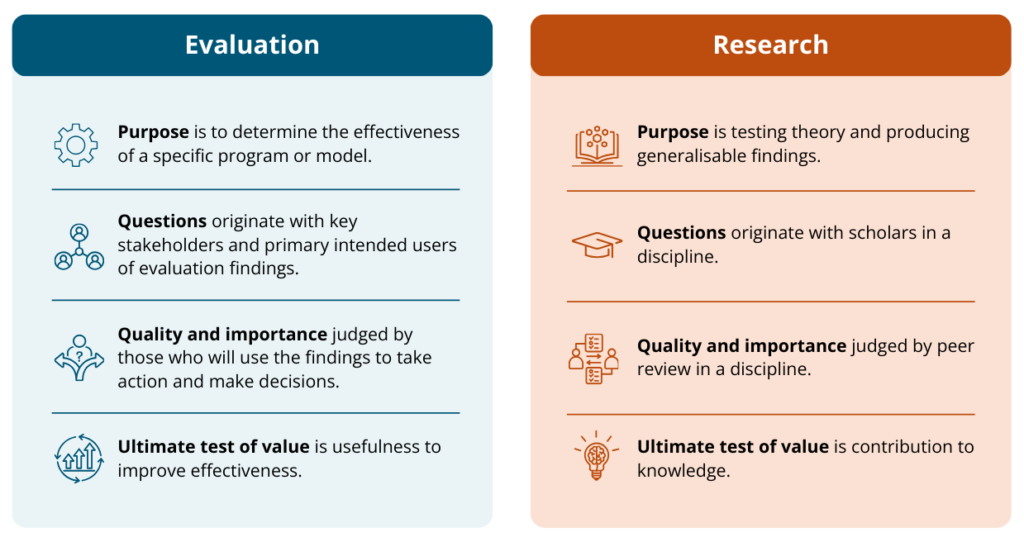

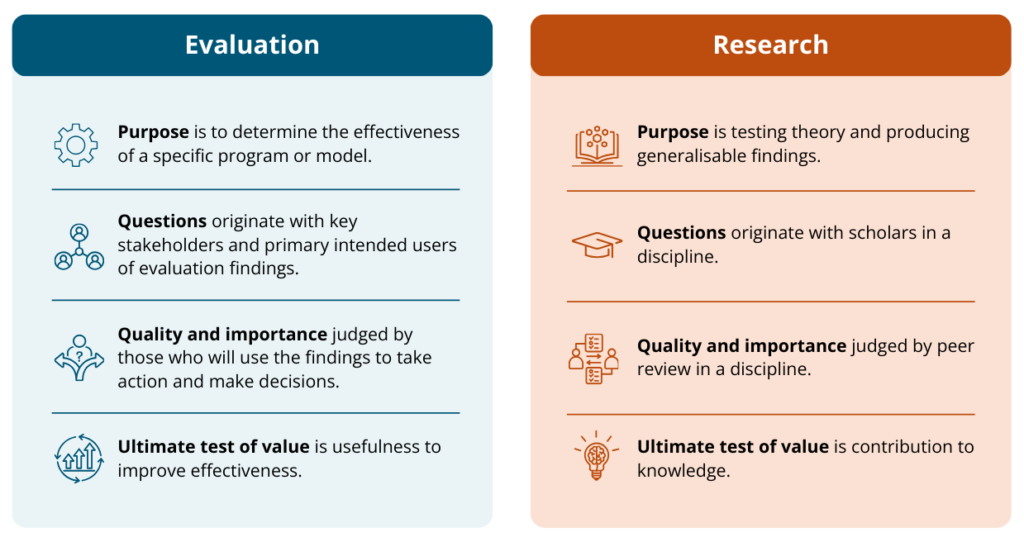

Evaluation and research both involve a process of systematic investigation. But they have different purposes.

Evaluation theorist Michael Scriven defined evaluation as ‘the process of determining the merit, worth or value of something.’[2] It’s about providing specific and applied information to better understand and improve the effectiveness of a course of action. The arbiters of an evaluation’s worth are those taking the course of action (not usually other evaluators).

But the ultimate purpose of research is theory testing and producing new knowledge, and its merit is judged by other researchers in that field[3].

Some of the differences between the purpose of evaluation and research, and how these impact their focus and use, are outlined below.

Source: Michael Quinn Patton (2014). Evaluation Flash Cards: Embedding Evaluative Thinking in Organizational Culture. St. Paul, MN: Otto Bremer Foundation. Available at: https://ottobremer.org/news_stories/evaluation-flash-cards/

The differences between the purpose of evaluation and the purpose of research mean that research questions and evaluation questions are framed in different ways.

Evaluation questions are evaluative. They require the evaluator to make a judgement about how good the program was, or how well it was done. For example, an evaluation of a program to improve students’ mental health through physical activity might ask:

Research questions are framed more neutrally and generally – they require the researcher to draw conclusions about how things work in the world, rather than being focused on a particular program or strategy. For example:

It’s important to note that both research and evaluation need to ask descriptive questions too. Both the examples above would be interested in finding out about students’ physical activity levels and mental health. The evaluation would be focused on the students in the target population of the program, whereas the research project would attempt to define and study a representative sample of the high school students in Australia.

This is where, in our view, there is the greatest overlap between research and evaluation: the process of collecting and analysing data. Similar methods might be used to recruit students to the example program above, as well as to measure their physical activity levels and assess their mental health.

In evaluation, the time and resources available for data collection and analysis are usually more constrained, and tend to be set by the commissioner, rather than by the evaluator. In research, time and resources are usually more in the researcher’s control—to a degree (research funding is highly competitive).

If the program budget is modest, the evaluation budget is usually also modest (unless scaling up is being considered, or if the program is particularly risky or innovative). Timeframes may be driven by fixed deadlines for re-funding decisions, or because the evaluation is feeding into a broader review. The timeframe and resources for evaluation are generally determined by the program owner rather than the evaluator, and may narrow the choice of feasible methods.

Evaluation findings can be used to improve how a program is working, to decide about future funding or expansion, or to provide accountability for funding already spent. The end result is usually a findings report to the program owner or evaluation commissioner. In the interests of transparency and to share information about effective practice, the report may also be published.

Publication is the key driver for research projects, since this is the main way that new knowledge is communicated. Research findings can be shared in journal articles, industry reports, conferences or other channels.

The biggest risk (for evaluators) is when evaluation commissioners who have research backgrounds set research questions, not evaluative questions. If the difference between evaluation and research is misinterpreted, the importance of making an evaluative judgement may be underestimated and result in a failure to draw useful conclusions based on all the data. This makes it more difficult, and in some cases impossible, to do that final evaluative step: determine the merit or worth of the evaluand. This diminishes the evaluation’s utility in informing decisions regarding the program or service.

Misunderstanding the difference between research and evaluation may also create unrealistic expectations for both commissioners and practitioners about methodology – both what can be achieved within the available time and budget and what is necessary for the particular program and decisions that need to be made.

What questions do you most want answered? What is best answered using an evaluation, and what might be better answered by research?

Don’t be scared to ask value laden questions!

Did we do a good job? How good? Is it good enough?

When planning an evaluation, part of the job is to make explicit with program owners and stakeholders, what is considered ‘good’. Clearly articulating the parameters of how worth will be measured is often harder than it sounds.

Know the difference between an evaluation question, a descriptive question and a research question and be able to explain the differences and why they are important. Collaborate with clients to reshape questions where necessary, as doing so will ultimately lead to a more usable outcome for the commissioner.

Don’t be scared to make an evaluative judgement when answering key evaluation questions!

Of course, that judgement should be based on careful interpretation of evidence that has been systematically collected and rigorously analysed. The evidence behind your judgement should be clearly explained (so readers can decide whether they agree). And if you don’t have sufficient evidence for a conclusive finding, then you shouldn’t make one. But remember that evaluative conclusions should not shirk from judging worth. Don’t just present all the data – the people who’ve commissioned the evaluation need to decide what to do, and they need your sound judgement about what it all means.

When you’re prioritising the use of evaluation resources, think about the decisions that need to be made on the basis of the evaluation results. The evidence you collect will need to be robust enough to make those decisions with confidence.

[1] Levin-Rozalis, M. (2003). Evaluation and research: Differences and similarities. The Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, 18(2), 1–31, 2.

[2] Scriven, M. (1991). Evaluation thesaurus. 4 th ed. Sage, p. 139.

[3] Davidson, J, Evaluation Methodology Basics: The Nuts and Bolts of Sound Evaluation (SAGE Publications, US, August 2004).